The Sudden Oak Death (SOD) epidemic in East Bay Park District forests dominated by coast live oaks, Quercus agrifolia, and bay laurels, Umbellularia californica, presents major management challenges. Coast live oaks play a disproportionately large role in these forest ecosystems even when they are not the dominant overstory tree species. There are no other tree species in these forests that support as many other organisms (insects, bird, mammals, and fungi) as well as produce high quality protein in the form of acorns. In addition to problems faced by other forests at the urban-wildland interface, such as invasive plants and degraded habitats, managers of these lands must now contend with the effects of Phytophthora ramorum, the pathogen that causes SOD.

Figure 1. In coast live oaks, sudden oak death exhibits a predictable, progressive sequence of symptoms.

Phytophthora ramorum is a water mold apparently introduced through the nursery trade from Asia. This organism, unknown prior to 2000, infects a remarkably large number of native plant species, causing different diseases in different species (Rizzo and Garbelotto, 2003). Typically these infections take the form of leaf or stem lesions and are not fatal. However, most oaks native to California that are in the red oak group (section Lobatae), which includes coast live oaks, are highly susceptible to the pathogen. Infection in oaks follows a consistent sequence: 1) a viscous exudate, referred to as bleeding, appears on the bark, typically no higher than about 1.5-m above the soil; 2) both ambrosia and bark beetles tunnel into these infected patches (often 10-15 cm deep into the sapwood); 3) fruiting bodies of fungi appear on the bark above the beetle tunnels; and 4) tree death follows (Figure 1). Because of beetle and fungus damage, up to 25% of infected coast live oaks may fail while still alive, typically snapping within 2-4 feet above the soil (McPherson et al., 2010). In the course of maintaining long-term study plots in Marin County, we have identified critical parameters for understanding the response of coast live oaks to infection by P. ramorum (McPherson et al., 2010) (Table 1).

Table 1. Survival estimates (years + standard error) for coast live oaks infected by P. ramorum in two Marin County forests, 2000-2008, based on Weibull survival models (McPherson et al., 2010). CCSP: China Camp State Park; MMWD: Marin Municipal Water District.

|

Disease Stage |

Median survival, CCSP |

Median survival, MMWD |

|

Asymptomatic |

15.8 (1.5) |

11.7 (0.8) |

|

Bleeding |

11.7 (2.7) |

7.5 (1.6) |

|

Bleeding + Beetles |

3.3 (0.4) |

2.0 (0.2) |

Management of forested ecosystems that are being affected by this introduced pathogen depends critically on understanding the magnitude of the threat. The Park District was aware that P. ramorum had been detected in their forests as early as 2001, but in the absence of knowledge of the distribution and severity of the problem, rational management plans cannot be developed. Beginning in 2009, with funding from the Park District, a team consisting of David Wood, Greg Biging, Maggi Kelly, Brice McPherson, and numerous field workers initiated a project to map the location and severity of SOD in coast live oaks in the five major forested parks that lie along the East Bay Hills using a network of permanent plots. These parks are Wildcat Canyon and Tilden Regional Parks, Huckleberry Regional Botanic Preserve, and Redwood and Anthony Chabot Regional Parks. These all lie directly east of densely settled Richmond, El Cerrito, Berkeley, Oakland, and San Leandro. The goal of this study is to develop models of change in disease incidence and severity and to predict future stand characteristics.

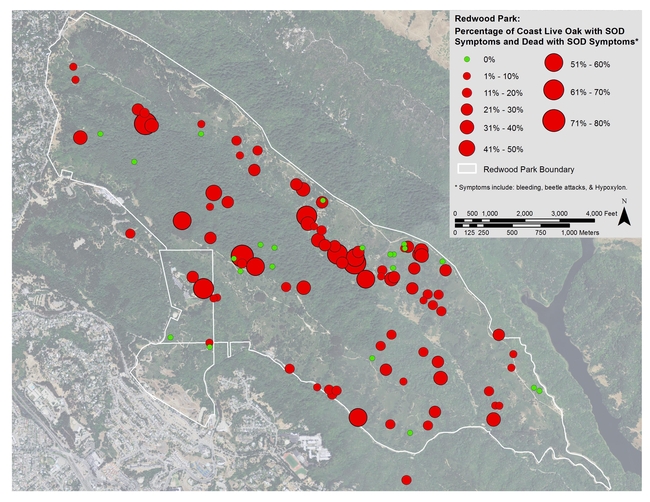

Figure 3. Plots in Redwood Park with both symptomatic and dead coast live oaks. Image produced by Sam Blanchard, GIF Berkeley.

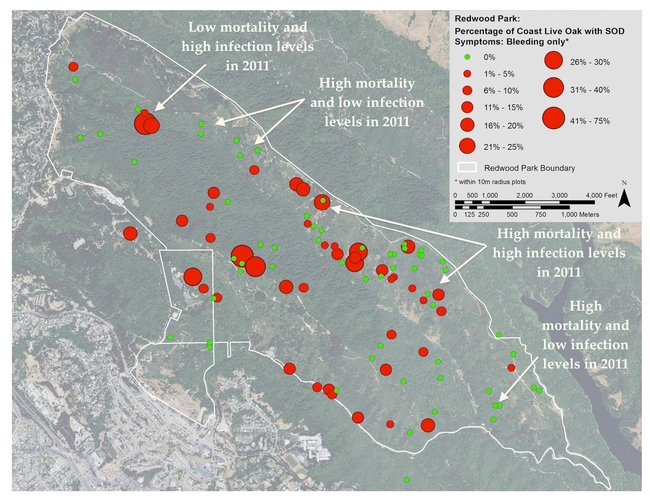

Analysis of the Redwood Park survey data illustrates this approach. We used geographic information system (GIS) technology and GPS devices to locate 105 plot sites randomly assigned within oak-bay habitats that were identified by vegetation type maps. Stand characteristics recorded for each plot include stem diameter at breast height (DBH) for every woody plant >2 cm DBH, health of each stem, and recruitment of woody plants, estimated by counting the seedlings and saplings in two linear transects. Dead, previously infected trees are reliably identified by extensive beetle tunneling and associated fungal activity.

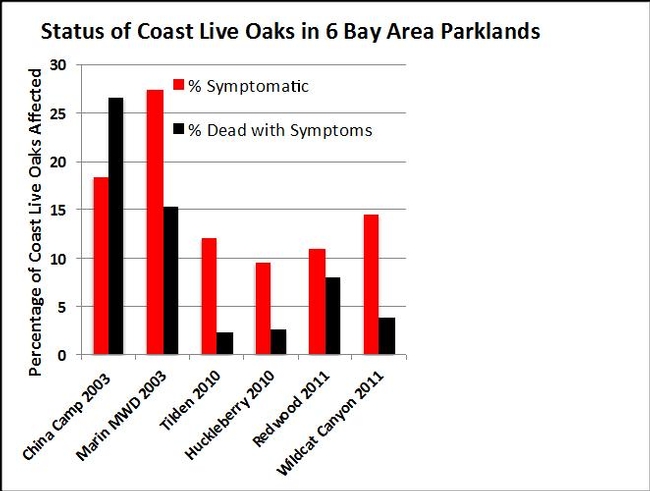

In Redwood Park in 2011, 19% of the coast live oaks in plots were symptomatic or killed by SOD. Comparison with the situation in Marin County in 2003 implies that considerably greater impacts are yet to come in East Bay forests (Figure 4). Resulting maps for Redwood Park show large spatial variation in the presence and severity of infected coast live oaks and differences in the proportions of trees in different stages of the disease (Figures 2 and 3). Note that in 2011 there were areas in Redwood Park with little or no actively detected bleeding coast live oaks (green) but with trees already killed by SOD. Because SOD is a progressive disease (i.e., unidirectional), knowledge of the distribution of the disease stages can be used to project stand-level change and to infer the history of the disease at a site.

Figure 4. Percentages of coast live oaks with symptoms of P. ramorum infection and those that died with these symptoms. The year indicates when each survey was done.

The data for the different stages of SOD will be used to develop a predictive model to facilitate management of these forests as the epidemic continues and expands into previously unaffected stands. Although no cure or treatment is likely to prevent further wildland infections and mortality, the ability to make data-based predictions at the landscape scale will enable planning decisions to be based on a factual foundation.

This work was initiated in collaboration with Nancy Brownfield, East Bay Regional Park District IPM Specialist, who died recently. Her presence will be missed.

References

McPherson, B.A., Mori, S.R., Wood, D.L., Svihra, P., Kelly, N.M., Storer, A.J., and Standiford, R.B. 2010. Responses of oaks and tanoaks to the sudden oak death pathogen after 8 y of monitoring in two California forests. Forest Ecology and Management 259: 2248-2255.

McPherson, B.A., Mori, S.R., Wood, D.L., Storer, A.J., Svihra, P., Kelly, N.M., Standiford, R.B. 2005. Sudden oak death in California: Disease progression in oaks and tanoaks. Forest Ecology and Management 213:71-89.

Rizzo, D. M., and M. Garbelotto. 2003. Sudden oak death: endangering California and Oregon forest ecosystems. Frontiers in Ecology and Environment 1:197-204.